2021 did not augur well for many in Southeast Asia. One month in, a military coup occurred in Myanmar, implemented by generals who were humiliated at the ballot box the previous November, ousting the democratically-elected National League for Democracy (NLD). Democracy since then, like many who participated, now rots in a prison cell. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), almost 1,500 people have been killed by the junta in 2021, and more than 8,300 have been arrested, charged, or sentenced for often dubious reasons.

While Thailand’s military coup surpassed its seventh year, it was no less consequential. Early last year brought a deluge of lèse majesté charges against pro-reform, pro-democracy protesters, a theme that still remains. Eager to control the masses, Thai police became more and more the enforcers of the Thai regime. Police brutality, marked by aggressive tactics by officers as well as the ubiquitous usage of purple-colored water cannons laced with tear gas. Worse yet, during the COVID-19 pandemic, following a common course by authoritarian rulers in the region, Thailand securitized its response, issuing decrees that attempted to both limit criticism and prevent mass mobilization. All of this occurred while prominent human rights defenders and pro-democracy protesters languished behind bars.

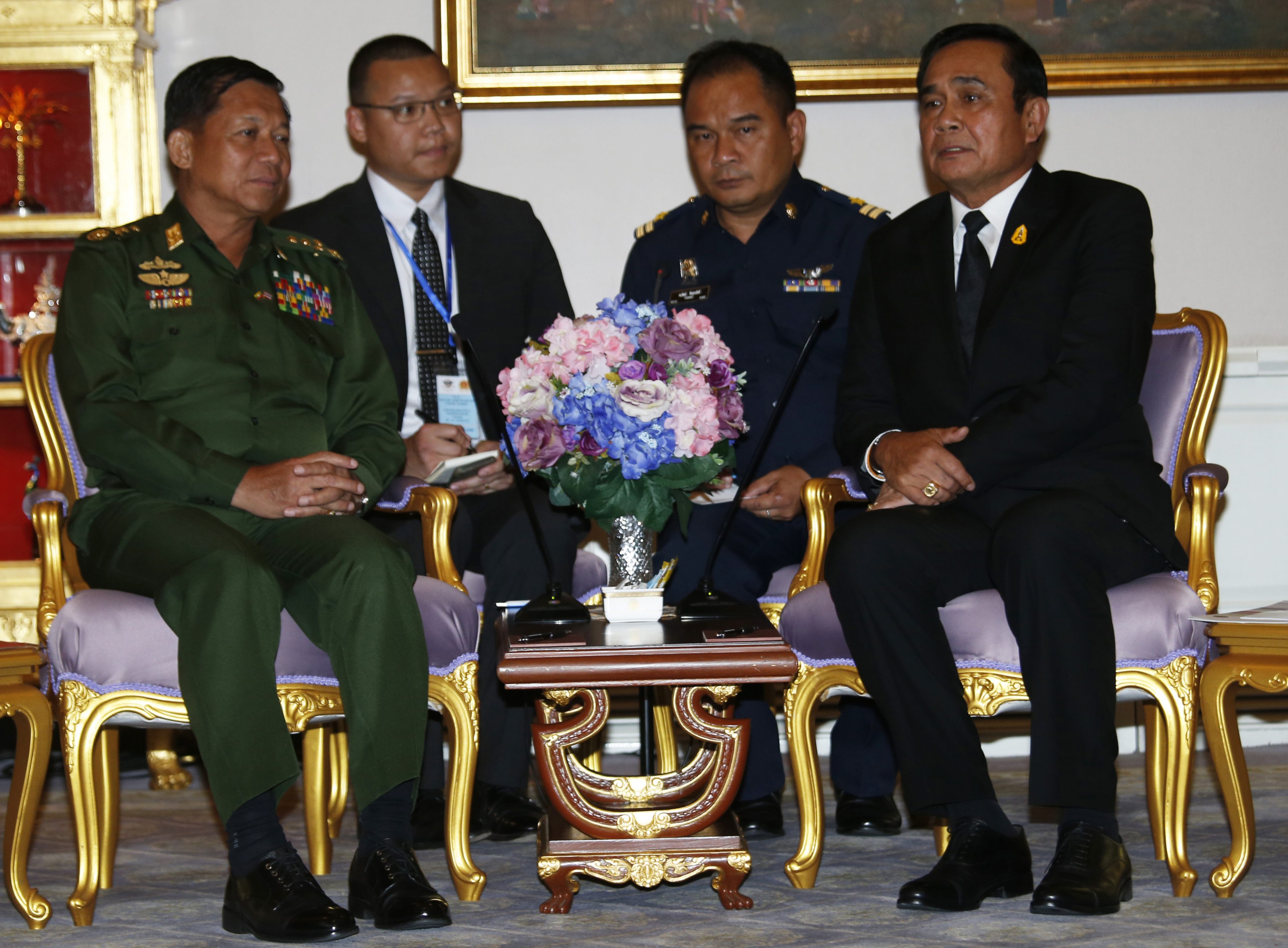

For broader Southeast Asia, this brief introduction does not encompass the decay of democratic freedoms and human rights abuses that the past year brought. Jointly, however, the broader ASEAN community will become a part of a bleak 2022, where human rights will remain in a state of decline, while democracy will remain a distant target in an ocean of regional autocracies. Cambodia, for example, assumed the ASEAN chairmanship this year, and is prepared to invite the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s brutal military into the regional fold, evidenced late last year by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s personal engagement with Myanmar’s junta-appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wunna Maung Lwin.

This poses a challenge within the famously-hamstrung regional bloc, which has tentatively held ground on Myanmar, blocking its attendance at the ASEAN Summit last October and the ASEAN-China Summit in November. Giving legitimacy to, rather than isolating the junta’s leadership poses grave challenges to regional security. First, any departure from the five-point peace plan that was developed by ASEAN in April of last year would fracture any consensus within ASEAN, as well as the formula for diplomacy, in the form of a Special Envoy. Second, there is speculation that external pressure is driving Cambodia’s bilateral efforts, as China has sought a role for itself in peace discussions. The two countries have a long-standing relationship, which allows Hun Sen greater movement as well as the benefit from heavy Chinese investment. In exchange, Cambodia acts like China’s proxy. Most importantly, fissures in solidarity within a weak ASEAN enable Myanmar’s junta to delay any potential peace process, thereby prolonging human rights atrocities and exacerbating a regional humanitarian crisis.

The promise of elections in many parts of Southeast Asia aren’t reasons to hope for a resurgence in democratization in 2022. Cambodia, the Philippines, Thailand and others hold elections this year in some form, each with potentially huge drawbacks. First, Cambodia has been busy dismantling what was left of the democratic opposition, with mass trials of opponents beginning early last year. Opposition leader Kem Sokha, President of the now-defunct Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP) was accused in 2017 over allegations he and backers from the United States were plotting to overthrow the Hun Sen government. His trial begins on January 19. In Cambodia, only the thin veneer of democracy remains, with local commune elections due to be held in June. Unfortunately, the number of opposition parties that can contest the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) are small, weak, and very short on human and financial resources. It is unlikely that they will be able to contest in the more than 1,600 communes across Cambodia’s 25 provinces. Instead, Cambodia will continue to be a showcase for Hun Sen’s successor, the Prime Minister’s son Hun Manet. A graduate of West Point, the core CPP leadership has backed Hun Manet, even after Hun Sen called for opponents in a future election to guarantee electoral credibility.

More significant is the upcoming elections in the Philippines, where the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos is set to become the successor to outgoing strongman Rodrigo Duterte. Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. has recently taken a 20-point lead in a recent poll, with himself and Sara Duterte-Carpio, daughter of Rodrigo Duterte reaching 53 and 45 percent support respectively. Like Duterte, Marcos, Jr’s populist politics have drawn interest among young and overseas voters, who say they value his charisma and charm. After several years of human rights abuses, as well as a relentless war on the press under Duterte, the Philippines could easily be ensnared by another would-be, yet youthful strongman. Part of the reason for this is not only reverence for the old Marcos regime among locals, but the fact that national politics remains dominated by an elite political class. Corruption and bribery are par for the course and a culture of impunity permeates many of the country’s institutions. Finally, middle-class voters have little enthusiasm for democratic systems, preferring authoritarian leaders who can deliver results rather than through the machinery of the rule of law.

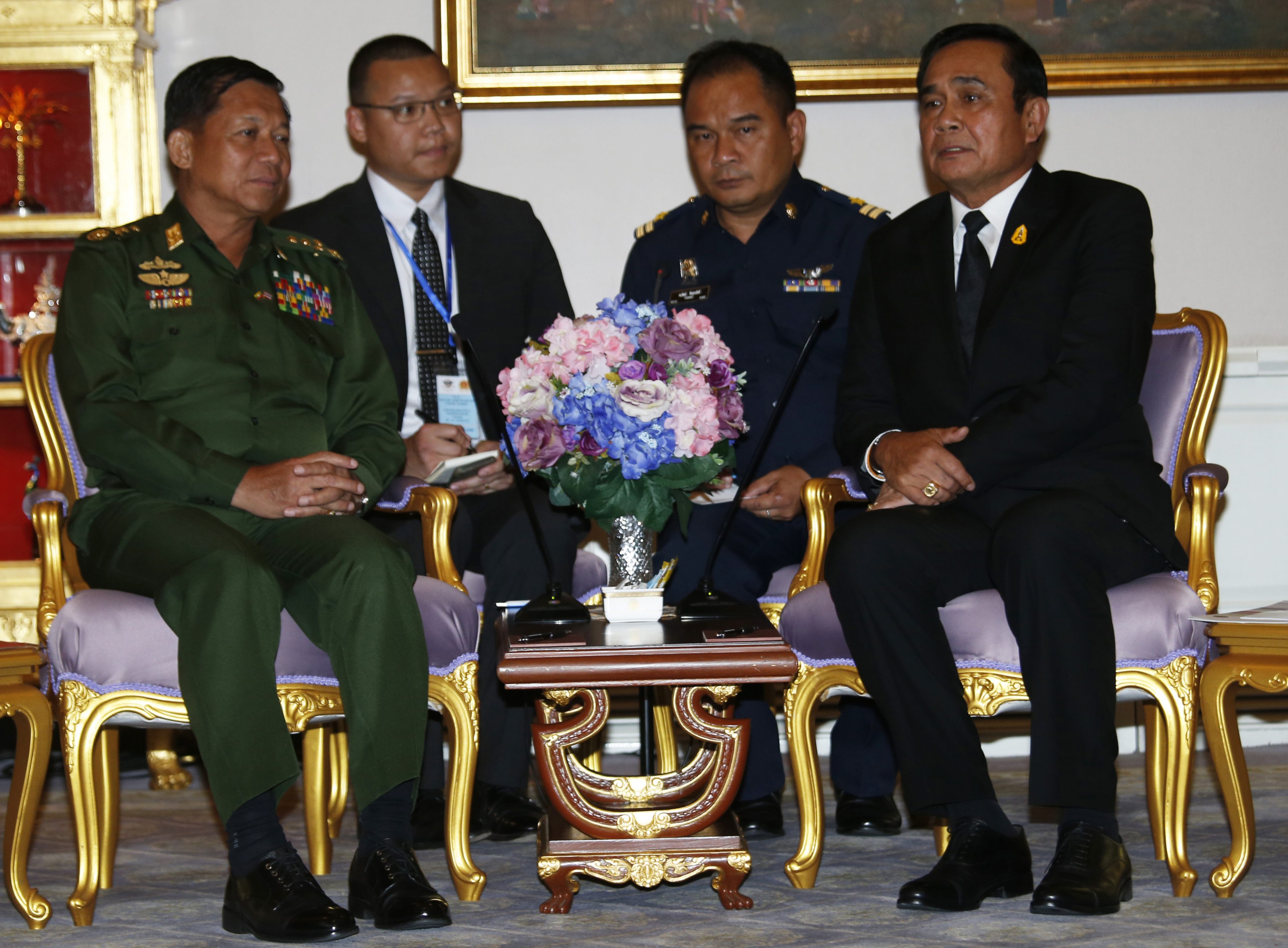

Domestically, Thailand has its own challenges, but the upcoming gubernatorial elections could be a rare problem for the Prayut Chan-o-cha government. The elections could be a thermometer, taking the political temperatures of a country that has not had a high-profile election since March 2019, although the contest was marred by a constitution that gave military-oriented parties significant advantages. Conventional wisdom suggests that the gubernatorial election will be a rare headache for the Palang Pracharath Party, which needs to secure support in Bangkok to sustain political momentum ahead of potential elections down the road. They have much to fear from the upstart Move Forward Party and main challenger, the Pheu Thai Party. Of course, Prayut holds a key card, noting that elections will occur only if the “situation is normal”. Broader issues, such as the extent of Prayut’s hold on power will likely not take shape until after 2022.

In the meantime, Thailand will face challenges to civil society, in the form of a draft bill aimed at reigning in Thai non-governmental organizations by requiring them to register with the Ministry of Interior. The law has received plenty of institutional backing from the National Intelligence Agency and the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. The bill, which has been slated for hearing this year, has been widely criticized by human rights groups, who claim that the bill would give the regime far too much control over civil society functions, including the monitoring of human rights abuses.

Challenges within Myanmar, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines are also shadowed by issues that transcend regional borders, such as damage caused by upstream dams on the Mekong River, a general sense of malaise about the hope for democratic revival, and a scourge of anti-press sentiment among ASEAN governments. 2022 portends very little hope for democracy and respect for human rights in Southeast Asia. A brutal 2021 all but eliminated any prospective recovery.