Every four and a half years, all 193 United Nations member states have their human rights records examined in a peer-reviewed process known as the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). In November, this will mark Thailand’s third time through the UPR, with the 2016 review occurring around the less than auspicious second anniversary of the May 2014 coup d’état. Back in February, in preparation for this upcoming human rights review, Thailand’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Don Pramudwinai gave remarks during the 46th Session of the Human Rights Council, noting that Thailand would “recommit to our common core values in the promotion and protection of human rights”.

To the Foreign Minister, that meant a rededication to the Sustainable Development Goals and Thailand’s Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP), promoting health as a basic human right, and working through the Human Rights Council to build a “strong, multilateral human rights system”.

Public statements on Thailand’s human rights contributions often boast about the kingdom’s accomplishments from achieving a reputable universal health care scheme, committing to end statelessness by 2024, or implementing reforms that will impact labour in the fishing industry. But these goals and accomplishments often mask Thailand’s true record on the ground – a record stained by draconian measures to cripple individual freedom of expression, curb press freedom, and silence regime critics.

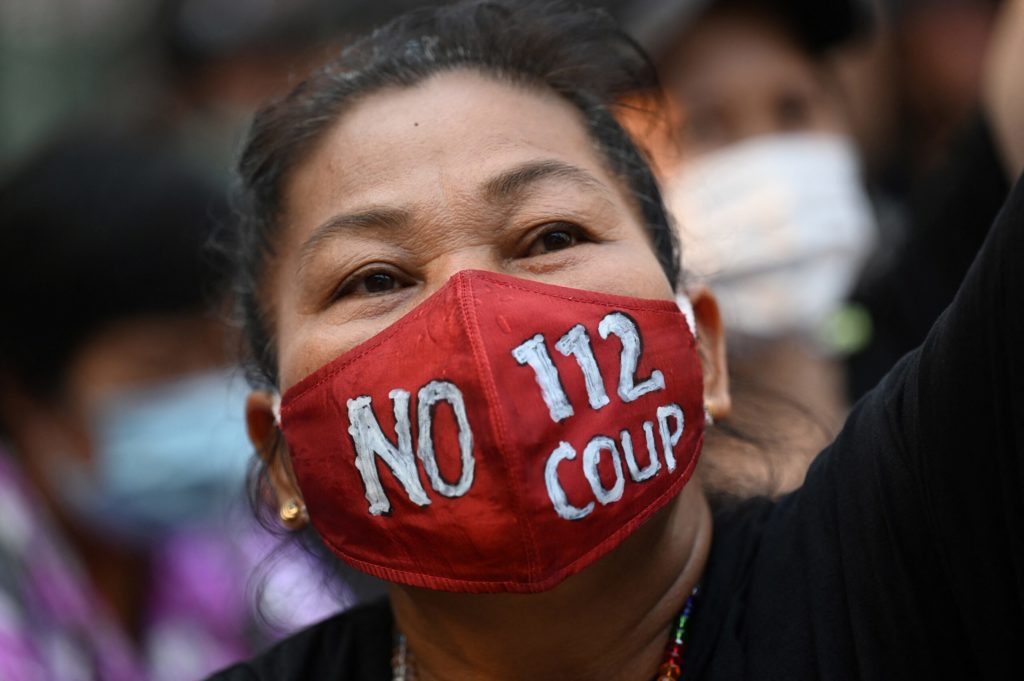

As cases of lèse-majesté pile up and pro-democracy protesters face other serious charges like sedition, one would expect the government to abandon the notion that it can pretend these challenges are minor. However, the government isn’t blind to realities on the ground. It simply ignores them.

At the diplomatic levels, Thai representatives to Permanent Missions to New York and Geneva are of the highest caliber. These representatives often serve on any number of commissions or working groups within the confines of the UN and maintain a high degree of visibility for the country. At the more senior levels, cooperation is often smooth and diplomatic relations are more than just cordial. Only when words strike caution among them that UN officials will hear common retorts, such as their perceived failure to understand what it means to be Thai, their lack of familiarity with the situation on the ground, or the more nationalistic refrain that highlights Thailand’s unique status as a country in Southeast Asia that has not been colonised.

When three UN officials met with the Foreign Minister sometime after the 2014 coup, the long-serving Thai diplomat wanted to ensure that the narrative on human rights was crystal clear to the UN – there were no human rights challenges in Thailand.

The Foreign Minister told them about Thailand’s accomplishments over the past several decades. He noted Thailand being an early signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, that in 2010 it had not only been elected as a non-permanent member of the UN Human Rights Council, but Thai diplomat Sihasak Phuangketkeow became President of that same body. He also remarked that Thailand was constantly working to gain positive results out of the US State Department’s TRIP reports.

Don Pramudwinai’s lecture continued for as long as 40 minutes. After trying to ensure that the trio also understood Thai culture and tradition, the Foreign Minister paused and remarked: “Actually, in summary, Thailand has one of the best human rights records in all of Southeast Asia.”

The UN officials were cautious going into the meeting and were somewhat prepared for a situation like this.

“When a Minister says something like, ‘We have a very good human rights record,’ if you even [nod] that is like acknowledging what he says, so we didn’t say anything,” said one UN official.

The Foreign Minister, because of the lengthy silence on the part of the UN officials, corrected himself and said: “No, no, no, Thailand has the best human rights record in Asia.”

Again, dead silence.

After the meeting, when a reporter asked the Foreign Minister if they discussed human rights, he simply smiled and said: “Human rights? We did not discuss that because it was not on the agenda.”

For the most part, diplomatic relations flourish at the senior levels, as that is often where the visibility is the highest and results are often spotlighted. Practical issues such as project implementation are often public relations winners for the government and the UN, and issues that cause less friction like forest protection, transnational crime, drugs, and illegal weapons can easily demonstrate results.

In Thailand’s national report submitted for its second cycle UPR in 2016, the Thai government compared its lèse majesté law (Article 112) as comparable to libel law for commoners, adding that it is “not aimed at curbing people’s rights to freedom of expression or academic freedom” and it was implemented in “accordance with due legal process and those convicted are entitled to receive royal pardon”.

Yet, the Thai junta and the current government have a history of taking hardline approaches to those charged with Article 112. Many, including Prawet Prapanukul, a human rights lawyer, were locked up in prison after being held at the 11th Army Circle base in Bangkok, a place the military often used as a temporary prison. Due process for cases like these is often inconsistent at best.

When a number of UN experts this past February sounded alarms over the harsh sentence of Anchan Preelert, a 60-year old former Thai civil servant who was given a 43-year sentence for insulting the Thai royal family, the Foreign Ministry responded to UN concerns, as well as reservations about the detention of a minor, by making the exact same argument it did in the 2016 national report. The Ministry noted that the law is not “aimed at curbing people’s rights to freedom of expression nor the exercise of academic freedom or debate about the monarchy as an institution”. The Ministry went on to suggest once again that the law exists to “protect the dignity of royal families in a similar way a libel law does for any Thai citizen”.

During the 2016 UPR, civil society organisations complained about Thailand’s unfair application of Article 112. The UN Country Team, which comprised all of the UN agencies present in Thailand, noted that the military’s National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) had issued a number of orders restricting freedom of expression, as well as arresting individuals under lèse majesté. That same year, countries like Latvia, Spain, Norway and the US made specific recommendations to Thailand regarding its application of the law, but all were merely “noted” rather than “supported” by the Thai government.

Thailand’s third time through the Universal Periodic Review, because of its predetermined narrative about its own human rights record, will most likely be as inconsequential as its previous UPR. Instead, the work of examining Thailand’s progress in meeting its human rights obligations will be left to slow, painstaking diplomatic channels and progress will be measured by cooperation on far less abrasive issues.

For the most part, diplomatic relations flourish at the senior levels, as that is often where the visibility is the highest and results are often spotlighted. Practical issues such as project implementation are often public relations winners for the government and the UN, and issues that cause less friction like forest protection, transnational crime, drugs, and illegal weapons can easily demonstrate results.

In Thailand’s national report submitted for its second cycle UPR in 2016, the Thai government compared its lèse majesté law (Article 112) as comparable to libel law for commoners, adding that it is “not aimed at curbing people’s rights to freedom of expression or academic freedom” and it was implemented in “accordance with due legal process and those convicted are entitled to receive royal pardon”.

Yet, the Thai junta and the current government have a history of taking hardline approaches to those charged with Article 112. Many, including Prawet Prapanukul, a human rights lawyer, were locked up in prison after being held at the 11th Army Circle base in Bangkok, a place the military often used as a temporary prison. Due process for cases like these is often inconsistent at best.

When a number of UN experts this past February sounded alarms over the harsh sentence of Anchan Preelert, a 60-year old former Thai civil servant who was given a 43-year sentence for insulting the Thai royal family, the Foreign Ministry responded to UN concerns, as well as reservations about the detention of a minor, by making the exact same argument it did in the 2016 national report. The Ministry noted that the law is not “aimed at curbing people’s rights to freedom of expression nor the exercise of academic freedom or debate about the monarchy as an institution”. The Ministry went on to suggest once again that the law exists to “protect the dignity of royal families in a similar way a libel law does for any Thai citizen”.

During the 2016 UPR, civil society organisations complained about Thailand’s unfair application of Article 112. The UN Country Team, which comprised all of the UN agencies present in Thailand, noted that the military’s National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) had issued a number of orders restricting freedom of expression, as well as arresting individuals under lèse majesté. That same year, countries like Latvia, Spain, Norway and the US made specific recommendations to Thailand regarding its application of the law, but all were merely “noted” rather than “supported” by the Thai government.

Thailand’s third time through the Universal Periodic Review, because of its predetermined narrative about its own human rights record, will most likely be as inconsequential as its previous UPR. Instead, the work of examining Thailand’s progress in meeting its human rights obligations will be left to slow, painstaking diplomatic channels and progress will be measured by cooperation on far less abrasive issues.